Coyote Buttes North ‘The Wave’ 2016

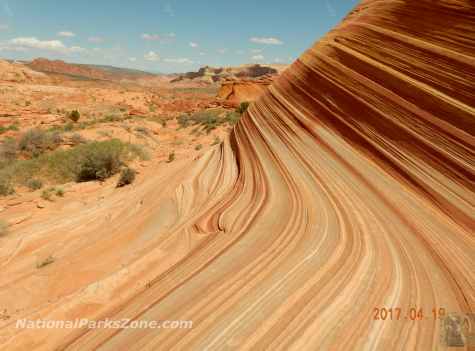

The Wave, officially known as Coyote Buttes North, in the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, is the most beautiful and interesting hike I have ever taken. Limited, at that time, by lottery to only 20 people a day, those lucky enough to secure a permit are rewarded with unbelievably beautiful sights that defy description.

Vermillion Cliffs, Utah -

2016

A Perfect 10 Hike

In May 2014, when I was in Kanab to go to Coyote Buttes South and White Pocket, there was the daily lottery at the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) office in Kanab, Utah for Coyote Buttes North at 9 A.M. and a lottery for Coyote Buttes South at 10 A.M. I was in the lottery for The Wave (north) for four days and came up empty. The fourth day was a last minute thing. We had checked out of the Comfort Inn next door (since taken over by Quality Inns) and were planning to drive to, and stay in, Ely, Nevada that night on the way to Lake Tahoe. It was a few minutes before 9 A.M. So we went in and ‘resurrected’ our application from the day before. They keep applications for 24 hours so you don’t have to fill anything out again; just give them your name, or the previous day’s number you were assigned, and they give you a new number and you are in for that day’s lottery (for a permit for the next day). At 9 A.M. they start drawing numbers from a hand-

After being in the lottery for just about two years I finally got lucky and secured two slots for May 4. Since we were going to go out there for the hike, and since we are quite familiar with the area and love it, we planned a 10 day trip. We spent three nights in Page, Arizona and toured lower Antelope Canyon and then headed to Kanab. Unfortunately my wife caught a cold on the plane trip out on Saturday and wasn't quite 100% by Wednesday when our permit for the Wave was. As luck would have it, of the 10 days that we were out there, that was the hottest day of all. The temperature was 80° and there wasn't a cloud in the sky. The slick rock radiates the heat which made it feel significantly hotter than the 80° temperature reading.

Nevertheless, trooper that she is and on medication and not wanting me to do the hike alone, we drove 44 miles down to the House Rock Valley Road turnoff and 8 miles further down a badly rutted road to the Wire Pass trail head. There we readied ourselves for the hike and proceeded to the trail head.

Since this is a designated wilderness area there's very little in the way of trail markings. Until three people died in the summer of 2013 I'm pretty sure they weren't any. In keeping with the wilderness designation any cairns hikers stack up are typically knocked down by BLM personnel. At this point there's about three ‘official’ markings. These are small square posts two inches on a side, less than 3 feet high and brown in color which makes them blend in nicely with the slick rock. When you qualify for a permit, and pay your fee, you get sent the permit in the mail along with a brochure with a map with GPS coordinates and two sets of pictures to guide you to the Wave. The first six pictures are of the trip out and they're easy to follow. The difficult part is the trip back and while the last six pictures will get you most of the way back it still wasn't crystal clear.

Heading out you hike the first half-

Once you've passed the Twin Buttes, in the distance, you can see what the brochure described as a vertical crevice. It appears as a black vertical line and right beneath it is where the Wave is. So once you see that line you just head toward it. I would estimate that it came into view a good mile and a half from it so you just needed to head toward it to get to the Wave.

At some point you leave the slickrock and cross a dune field down to a wash and you then scramble up a sand and slickrock hill to the entrance to the Wave.

While we had the misfortune, comfort wise, to be hiking on a bright sunny day we arrived there around noon so the sun was directly overhead which actually makes for better pictures. Since the wave itself is kind of nestled among the buttes, if the sun is lower in the sky, you are going to get more shadows. With a direct overhead sun the entire area is lit up without any shadows. This made for some great pictures.

We took lots of pictures and walked around and marveled at the terrific job of sculpting the Navajo sandstone that nature did and I enjoyed every minute of it. Unfortunately my wife's cold had taken its toll and hiking 3+ miles across the desert had left her somewhat drained and less than enthusiastic about spending lots of time out there in the sun exploring the entire area which covers about 2 acres. We did find one shady spot where we sat and ate our lunch and got ourselves ready for the trip back.

On the hike back the first landmark you look for, once you cross the wash and the dune field, are the Twin Buttes in the distance. You head for them and once you pass them you're now looking for the small saddle that you crossed on the way in. There is a pointed butte to the right of the small saddle which is the landmark that you head for since the small saddle really doesn't stand out. It definitely doesn't look the same heading back as it did going out.

When I reached the small saddle, and I wasn't sure it was the small saddle, there was one of the few trail markers that gave you the option of heading over the saddle or to the right of the saddle to get back. I figured I could go to the right of the saddle and go either way when I reached the other side. On the other side directly in front of me I could see a wash and lots of tracks heading up the far side of the wash. I just assumed that both ways that the trail marker pointed was going to lead me to that trail. Had I climbed up the saddle I’d no doubt have seen another trail to the left going up from the wash -

I do have to say that when I was out there unsure if I was on the right track, and seeing that my wife was not 100%, I became acutely aware of how dangerous this hike could be. If you run into trouble, someone starts to suffer from heat exhaustion, or is bitten by a snake, there's no one to help you, no cell phone service and rescue is hours away. If someone collapses, and you're the only person with that person, what do you do? On the entire hike out and the entire hike back we never saw another person. The only people that we saw were about eight people out at the Wave. Most people want to maximize their time out there with the intent of leaving enough time to hike back in daylight. You don’t want to be out in the darkness trying to find your way back when there isn’t any (well) marked trail. I realized later that there were two routes from the small saddle. The route we came in on which went over the saddle and was a shorter route and the route that I took back, what the brochure calls the alternate route, is the longer one. So the chances of somebody coming by that could help us if we needed help was very slim. By my calculations if I had to leave my wife to get help it would've taken me 45 minutes to get to the trail head where my car was, almost another half hour to go 8 miles up the dirt road to Highway 89 and then it was about 35 minutes, almost to Kanab, before I had cell phone service to call the search and rescue numbers that I had the foresight to program into my cell phone. How long it would take search and rescue to get out there and get to, or find, the person in trouble (if you didn’t have GPS coordinates to give them) is something I can’t speak authoritatively on. I would only speculate it could be a couple of hours and you have to add to that the time it took to get to cell phone service to make that call for help. That's a long time if someone is really in a life-

This is wilderness area and if you going to hike there the assumption is you should know what you're doing. Anybody who wants to apply for a permit can. And anybody who's been in the room when the lottery is held and looked around them knows that there's a lot of clueless people in that room. One can tell the experienced hikers from the clueless and each is entitled to the same chance at a permit. After three people died in the summer of 2013 some people were calling for changes but I don't think that's the answer. In one article they said that the 65-

When I was in the lottery in 2014, and aware that the preceding summer three people died, I was astonished that this fact was never mentioned by the BLM people running the lottery. There was little in the way of warnings. There was a gallon jug at the end of the table that said this is how much water each person should carry per day. If they checked each person at the trail head I’m sure 90% would not have that much water. At the end of one lottery I discussed this with a BLM person and questioned how they could not mention such a significant fact as people dying. He had no answer. However, when we were out at the Wave on this trip we met two girls who had gotten a permit the day before in the lottery and told us that, before the BLM took their application, they basically read everybody the riot act. They mentioned the deaths and the difficulty and dangers and the need to know what to do if you run into trouble. And the fact that you won't have cell phone service and rescue can be long in coming (and expensive!).

I believe that's the right way to handle this. This is a beautiful and unique place and part of the beauty is the solitude that you experience when you are there. Providing unlimited access would turn it into Disneyland and ruin it. Enough boot prints would create a darkened path through it and there is always going to be the idiots who carve their names into the fragile sandstone walls.

Hiking in the wilderness is about personal responsibility. It is about knowing your limitations and being prepared for the unexpected. If you are going to hike in the wilderness, or drive in the back country, you have to realize that, if you don't know what you're doing, you could be in a very serious, even life-

*Note* In 2021 the BLM increased the number of permits from 20 to 64 with 48 available in the monthly online lottery and 16 available at the Kanab BLM office lottery for the following day. Until then it was 10 online and 10 at the BLM office.

The Wave Photo Gallery - 2016

Other Resources

Recreation.gov -

The Wave -

Updated 02/11/23 7:04 PM

National Parks Zone